This article was originally published on the Gavi website. You can access the original article here:

How close are we to finding hepatitis B’s kryptonite?

How close are we to finding hepatitis B’s kryptonite?

VaccinesWork spoke to virologist Dr John Tavis about an approaching arsenal of therapies.

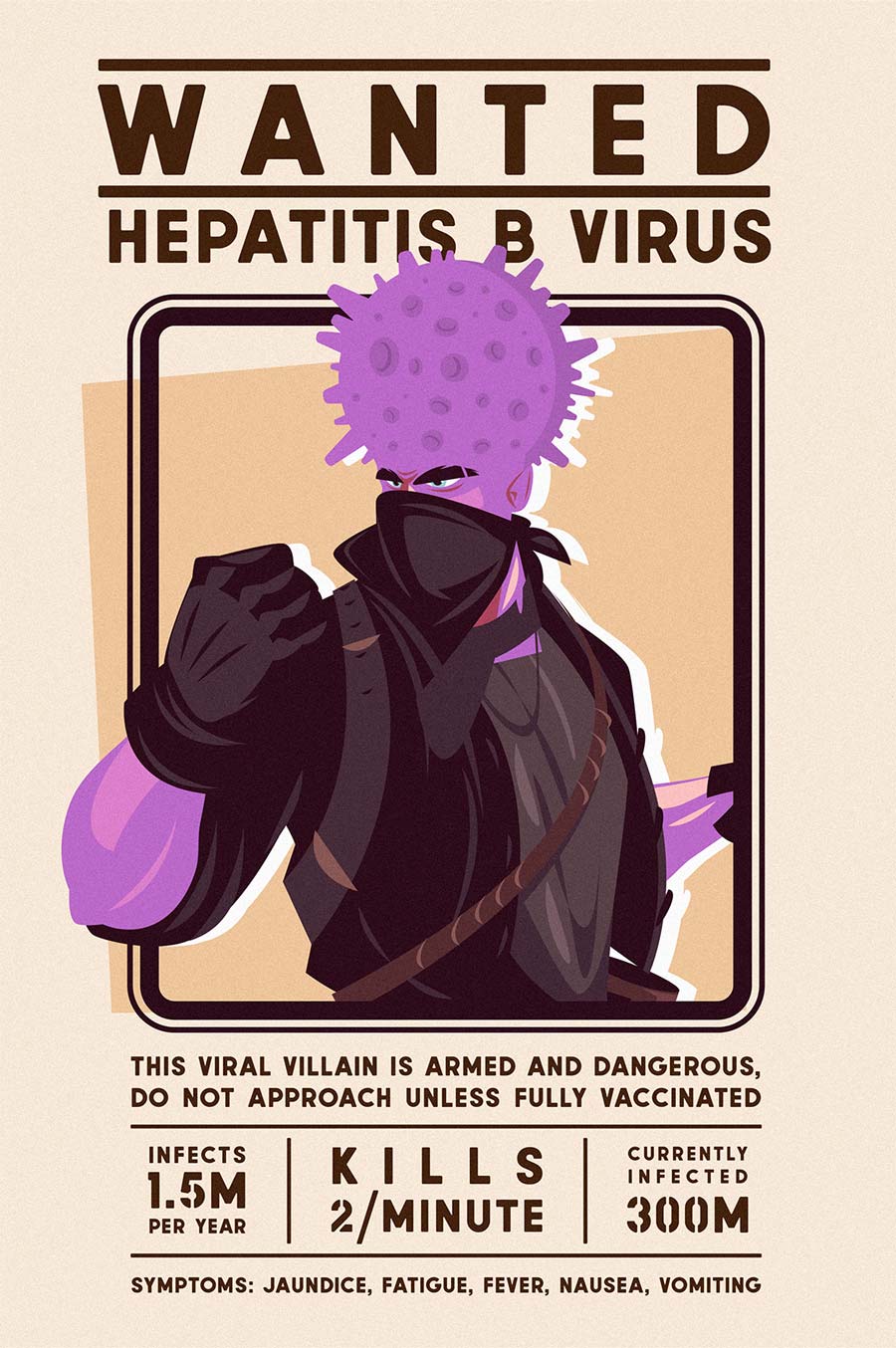

As far as viral villains go, hepatitis B virus (HBV) is among the most wanted. Claiming the lives of two people per minute, this ferocious disease has a hit rate on par with HIV/AIDS.

Seeping into the body through contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person, HBV latches onto cells in the liver, injects its DNA and hijacks the cell’s machinery to power its own replication. HBV is a silent assassin. It can hide out for decades, causing potentially life-threatening damage to the liver and spreading to new victims before any symptoms show – claiming the lives of more than 800, 000 people each year.

“It’s great we’ve got [these therapies] but it’s not where we need to be,” he says. “One class [of drugs] is hard to take, the other you need to take forever.”

HBV’s assault on the liver causes a disease called Hepatitis B (hepB). Most adults with hepB recover within one to three months after symptoms start, but when the infection persists longer than six months it’s considered chronic. As the virus attacks the liver cells, it leaves behind nasty scars called fibrosis. In up to one-third of the patients the scars become severe (cirrhosis), eventually resulting in liver failure or liver cancer. While hepB can be fatal, it is treatable, but it is also easily prevented to a degree of 95% through routine, safe, immunisation.

Upscaling vaccination, screening and treatment is the best way to keep this viral criminal at bay. New developments or scientific breakthroughs in any of these three areas is bad news for HBV, but good news for us. So, when scientists on the frontline say this deadly disease is about to meet its match, it’s great news.

Current treatment

Current HBV treatments interfere with a specific part of the viral lifecycle – stopping the virus from replicating and spreading. None of the current therapies stop viral replication completely, but they are able to slow down replication enough to reduce the risk of liver cancer and other diseases caused by HBV infection.

When no HBV DNA or proteins can be detected in the blood months after treatment stops, the patient is considered “functionally cured”, but small amounts of the virus can still lie dormant in the body. These “sleeping” viruses can still be “woken up” by medications that suppress the immune system.

There are two types of treatment. One uses nucleot(s)ide analogues: molecules that block the viral DNA from replicating inside the host cells. The other involves flooding the body with proteins called interferons, which switch on the body’s natural immune defences against the virus.

A patient receiving interferon treatment must have a dose injected each week for a year. Unfortunately, this treatment is taxing on the body, causing flu-like symptoms for days after it’s been administered, which can have crippling ramifications for work, social and family life.

Have you read?

Nucleot(s)ide analogue therapies are a much easier pill to swallow – literally. Taken in tablet form once a day, this treatment is preferred over interferon treatment because it has fewer side effects. However, nucleot(s)ide analogue therapy must be administered for long periods of time and is indefinite for most. This prolonged use of nucleot(s)ide analogue treatment can also lead to side effects like bone loss and kidney problems for some of the drugs.

Professor of Molecular Virology at the Saint Louis University School of Medicine, John Tavis, said only 5-10% of patients achieve a functional cure when using these treatments. This doesn’t mean the other 90% of people aren’t greatly helped by the treatments, but the extent to which the treatments reduce the presence of HBV in the body is not high enough to consider the patients functionally cured.

“It’s great we’ve got [these therapies] but it’s not where we need to be,” he says. “One class [of drugs] is hard to take, the other you need to take forever.”

The future of treatment

Chairman of the Scientific Advisory Council for the annual International Hepatitis B Virus Meeting and the Incoming Chair of the International Coalition to Eliminate HBV, Dr Tavis works on the front line of researching new developments in HBV treatments.

Dr Tavis says the cure to HBV is coming. “The feeling within the scientific community is that major improvements will happen somewhere in the next five to 10 years… [but] it isn’t going to be one optimal combination at first.”

“The best way to cure any disease is the one-two-punch,” Dr Tavis says. “It’s always better to stop a problem before it starts… [then] the drugs are needed as a mop-up crew.”

Instead of the cure being a singular treatment or a singular element, like the kryptonite that threatens to destroy Superman, Dr Tavis says the cure to HBV will likely be a collection of powerful tools that together will have the strength to take on the virus.

Scientists all over the world are making huge advancements in new treatments that can “attack the virus from every angle”, he explains.

Like a squadron of disease-demolishing superheroes, some of the therapies in development focus on blocking the virus entering the cell in the first place, whilst others deactivate the DNA. There is one therapy that will distort the shell of the virus so HBV becomes inactive and unable to survive. Another will lock itself to the genetic material of the virus and either cause it to fall apart or stop it from working.

Clinical trials are underway to investigate how these various treatments can be combined to work safely and effectively with one another, so healthcare professionals will be able to pick from a “toolbox” of therapies to deliver patient-specific treatment. One pharmaceutical company, Replicor, is already doing it. Using a three-part combination of drugs, Replicor is achieving a functional cure rate of 35% in early clinical trials.

“The one-two-punch”

Dr Tavis feels excitement about the advancing therapies and intense gratitude toward his colleagues and the scientific community. To keep this momentum, he said funding must continue to be pushed toward HBV research, so scientists on the home stretch can get to the finish line.

“There’s hope,” he said. “We need to push hard, and we need advocacy… we need to keep the motivation and support from governments and foundations around the world.”

Despite the excitement about the prospect of finding an HBV cure, vaccinating against HBV remains the single best way of vanquishing the virus, since the treatment is largely inaccessible for most HBV sufferers.

According to the Center for Disease Analysis, 96% of hepB cases occur in low-middle income countries, where communities struggle to access public health services due to a range of structural, social and economic barriers. It’s no surprise, then, that only 5% of global HBV sufferers are receiving treatment.

“The best way to cure any disease is the one-two-punch,” Dr Tavis says. “It’s always better to stop a problem before it starts… [then] the drugs are needed as a mop-up crew.”

More than two-thirds of the now 6.3 million children below the age of five with hepB live in 47 African countries. This is especially concerning since hepB becomes chronic in nearly 95% of infants and children who contract the virus, compared to only 5% of newly infected adults. In these countries, mother-to-child transmission – or vertical transmission – is the most common mode of way hepB is passed on.

To reduce vertical transmission of the virus, a dose of hepB vaccination is recommended within 24 hours of birth. In 2021, less than 20% of newborns across Africa received this birth dose of vaccination and only 14 countries in the region had national policies for hepB birth dose vaccination.

Earlier studies from Asia and North America have shown that the birth dose vaccination can reduce vertical transmission, however a lack of data from Africa on the effectiveness of birth dose vaccination contributes its low uptake in the region, where the epidemiological characteristics are different.

As a father of two sons who both grew up to become scientists themselves, Dr Tavis feels a personal connection to the importance of making HBV vaccines accessible to every child. Recalling the feeling of holding his sons as babies, and the parental instinct to protect their delicate human lives, he says, “You just want to put a force field around them to protect them, and that’s essentially what a vaccine does.”

“We need to go pedal to the metal on this. It needs to be 100% delivery.”